We’re BTS

Strategy made personal.

Inspiring and equipping people and organizations to do the best work of their lives.

BTS is a consultancy specializing in the people side of strategy. For over three decades we’ve been designing powerful experiences that have a profound and lasting impact on businesses and their people. We help the world’s leading companies turn strategy into results.

Our next-generation approach combines deep business knowledge with transformational development to help your people and your company evolve together. We equip leaders for tomorrow. We inspire new ways of thinking. We build critical capabilities. We make strategy personal.

In short: We unlock human and business success.

How we’re different

Business and people centric

We operate in the intersection of strategy consulting and people development. We meld deep understanding of your strategy and performance with our ability to create transformative experiences.

Unrivaled simulations

Our 30+ years as the global leader in modeling roles, businesses, strategies, cultures, and workflows will help your people feel included in the company’s direction and give your leaders the ability to practice the behaviors needed for your company to evolve.

Turning strategy into action

Our personalized journeys of learning, development, and execution, help people and organizations develop new habits, and come out stronger, better aligned, and more prepared to execute their strategies.

Client obsessed

Relentlessly contextual to your strategy and culture, we co-create our programs around the metrics and behaviors that will help you align your people and create positive results.

Mindsets are the key

Our programs work to break down the assumptions, biases, and beliefs within your organization generating mindset shifts that will quickly become the backbone of sustained change.

Services

Strategy execution & business transformation

A great strategy is worthless if it isn’t well executed. BTS equips and enables your leaders to drive the transformational change needed to bring your strategy to life and deliver incredible results at scale.

1 of 4

Services

Leader readiness & development

Today’s leaders must be transformational. BTS has the innovative tools and frameworks needed to help leaders practice and understand how to embrace change, take smart risks, meet employees where they are, and unlock the full potential of their teams.

2 of 4

Services

Go to market

Your sales, marketing, product, and service teams face multiple challenges and fragmented markets. BTS can help you connect and engage with your customers, accelerate customer decision-making and drive better business results.

3 of 4

Services

Talent acquisition & succession

Real-world experiences drive real-world results.

We believe context matters. Our assessments are about leading your business, not any business, and mirror the dynamics of your business and culture.

4 of 4

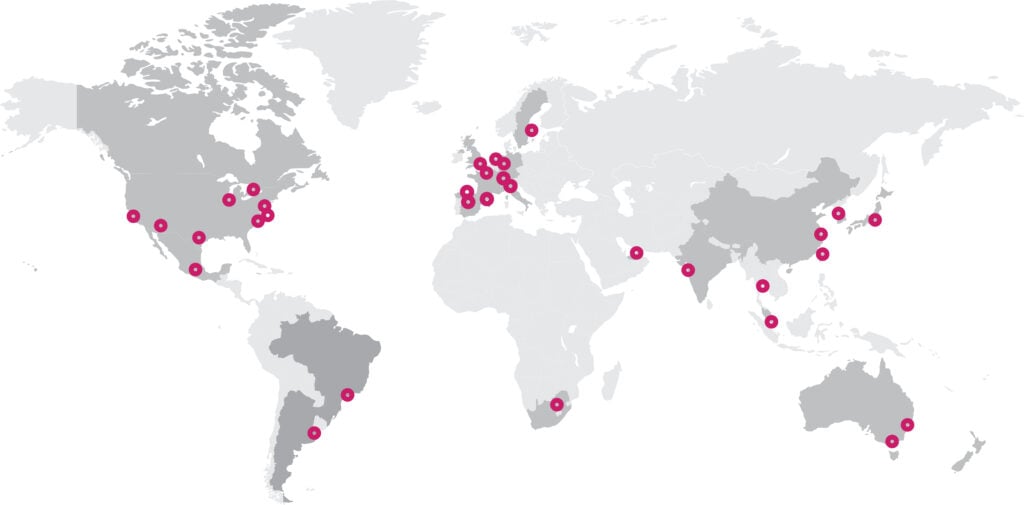

With 36 offices around the world, we understand your market and are ready to help you with your most challenging needs.

View all our offices

What’s trending

View all

Join us

Interested in joining the BTS team?

BTS is working to modernize business culture around the globe. We’re looking for creative, courageous, and empathetic individuals who want to help individuals and teams find a greater purpose in their work. We love what we do, and we think you would too.

1 of 1